Wangaratta - Bullawah Cultural Trail

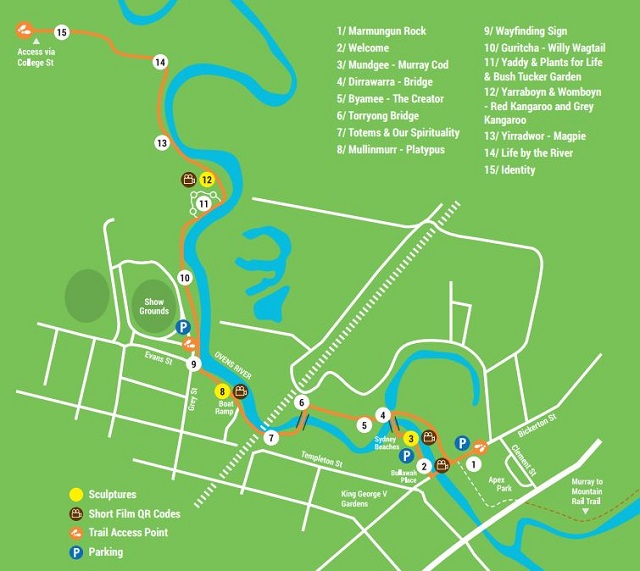

On this this self-guided family experience you will snake 2.4km along the Ovens River discovering ancient Aboriginal stories, spirituality, culture, food, sculptures, interpretive signage, the Marmungun Rock and the Bush Tucker Garden.

The Bullawah Cultural Trail was created to celebrate and share the ancient stories, knowledge and skills of our local Indigenous people. To delve deeper into the Aboriginal stories along the trail scan the QR codes featured throughout the trail with the QR code Reader on your phone.

The Bullawah Cultural Trail is accessible for cyclists, all ages and abilities. Download the self guided walk brochure here.

Route Map

Trail Points

1. The Marmungun Rock

Marmungun means 'of this group' or 'of this area' - the closest traditional Pangerang word for community. The Marmungun Rock concept was conceived by respected Elder Wally Cooper whose pride in his Aboriginal heritage and message of hope for the future inspired many. His ability to connect with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people has helped build respect, understanding and reconciliation.

During National Reconciliation Week, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community recognises the Wangaratta Citizen of the Year who has demonstrated the qualities of an Elder - community service, integrity and wisdom. These handprints are an enduring tribute to outstanding individuals in our community

2. Welcome

We are the Pangerang (Bangerano) people. Since time began, we have belonged to this county.

In our language, Bullawah [bulla meaning two and wah meaning water] signifies the two suspension bridges crossing the river as well as the joining of the two rivers and the coming together of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Wangaratta takes its name from our words: wanga meaning long neck and ratta meaning cormorant.

3. Mundgee - Murray Cod

Mundgee, the Murray Cod used to swim freely up and down Tongala (Murray River) and all its tributaries, including Torryong (Ovens River) and Poodumbia (King River).

As he grew in these rivers he found it difficult to turn around. He made turning circles and that's how the waterholes were made. When Aboriginal people draw or paint the rivers they include circles to denote the story of how the waterholes began.

4. Dirrawarra - Bridge

Dirrawarra is a Pangerang word meaning together and united.

Dirrawarra was adopted as the traditional name of the Local Aboriginal Network (LAN) to reflect the strength, pride and unity of the local Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, its values and its vision. Dirrawarra echoes the way the network and community work to achieve their goals by doing things together and by building partnerships that unite people.

5. Byamee - The Creator

Byamee, the Creator, came from a bright star to our land when it was dark, cold and without life. Byamee travelled the land, creating our perfect world, everything you see: every insect, every plant, every fish, every bird and animal. He created nungara (the sun) for light and warmth and goonie (the moon) to shine softly half the time. He created atmosphere to bring wallan (rain) to replenish the water supply. He created the trees, rocks, grasses and flowers. He created our people and asked what they needed. When he was satisfied with the world he had created for us, Byamee left and has never returned.

6. Torryong - The Ovens River

The sun glared and the thurgoon (earth) baked because there had been no wallan (rain). Gunyuk (the chief) asked the people of Juna (the snake) to call to their totem clan. They formed a circle, swayed side by side and sang the giant Rumbalara (rainbow serpents) down from the mountains. Gunyuk told the serpents to travel west for three days, then turn south to find water. The serpents formed one long line, carving a deep, twisting groove as they went. For three days and nights, Gunyuk and the clan sang to Byamee for rain. Rain came and flowed down the slopes into the grooves left by the snakes and created Poodumbia (the King River), Torryong (the Ovens River), which flowed into Tongala (the Murray River). The water flowed deep and wide.

Mary Jane Milawa

Mary Jane Milawa's Aboriginal name was Gunyuk (swan). She was the youngest minkan (sister) of Luana, who was the great grandmother of Uncle Freddie Dowling.

When they were very young, Mary Jane and Luana were accompanied by some Wiradjuri people from their homeland to live at a safer place at Lake Moodamoot (now known as Lake Moodemere).

But Mary Jane pined for her country and returned to live as a single woman along the river flats east of Wangaratta, between Wangaratta and where the town of Milawa is today. She died in 1888, aged about 60, and is buried in the Wangaratta cemetery.

This story was told to Uncle Freddie by his father and grandmother.

7. Totems & Our Spirituality

Nargoon (koala) is the tribal totem of our Pangerang people. A totem is a spiritual symbol - a natural object, plant or animal. Our individual totems are what keeps the biodiversity of our country in harmony. We give each boori (child) a totem at birth, passed on from their parents and ancestors.

Our spirituality

Land is the starting point from where everything in our world began. We don't own the land, the land owns us. We see our bodies as the land and our veins are the rivers that flow through us, nourishing us and sustaining life. We are spiritually connected to the land, like an artery and its tributaries - like the life-giving water that flows through the Ovens River and its tributaries, from the mountains, down across the plains and into the mighty Murray River. ~ Uncle Sandy Atkinson

8. Mullinmurr - Platypus

Born of mismatched love of Widjul (black duck) and Nunjarri (water rat).

The Mullinmurr (platypus) creation story is a fascinating and engaging tale that has an important place in Australian history. This artwork seeks to explore the playful side of relationships and suggests the inherent dangers of forbidden love. The design of the work was inspired by conversations with local elders to gain an understanding of Aboriginal culture and Australian wildlife.

The Mullinmurr story is linked closely with the river and can help us understand the importance of our role in caring for our environment.

9. Wayfinding Sign

The Dreaming is the environment in which our ancestors lived and continues in our spiritual lives today. It explains the beginning and continuity of life.

The Dreaming embodies our heritage, our connection to country, our relationships and our obligation to protect and preserve the spirit of the land and all life forms that are part of it.

Dreaming stories tell of our ancestors' beginnings and spirits who moved through the land.

Song Lines

Each tribe had their own boundaries. Our spiritual beliefs tell us where we can and can't go. We sing the song of the land to reconnect us to country, to our home, to our family, to our legends and stories.

For us, there is nothing like walking through our own country.

10. Guritcha - Willy Wagtail

Guritcha (the willy wagtail) and Deedreepah (the mudlark) each believed they were the bravest bird in the bush next to Yirradwor (the magpie). They agreed to a contest of bravery, wearing Yirradwor's black and white colours so all would know. Yirradwor would be the judge.

Boobook (the wise owl) told of a monstrous flood coming. Deedreepah bravely built his nest of mud right out on a limb over the river. Guritcha built his nest lower of cobwebs and hair he pulled from the back of animals.

At night when the flood came, Guritcha told his wife to take their babies higher in the tree. Next morning, the water lapped just below Deedreepah's nest where he had bravely stayed all night.

When the water dropped, Guritcha was found drowned, but still sitting on his nest. Under his body was a baby, still alive.

Yirradwor declared Guritcha the bravest bird in the whole bush. Guritcha's descendants still wear the black and white colours and pluck hair from the back of animals and bravely attack other birds.

11. Yaddy & Plants for Life & Bush Tucker Garden

Yaddy was a much-loved young Pangerang warrior recognisable by his long flowing hair. He was an expert in making boondithurra and currawon (spear shafts) from the roots of trees along the river bank. His wife Bunjeet and their children helped him.

When Yaddy and his family grew old and died, they were buried in the soft gravel of the ranges. Just before he died, Yaddy wished he could go on making spear shafts for his people. Byamee dearly loved Yaddy, so had an everlasting plan for him.

Years later, Pangerang people noticed a new kind of plant growing, the grasstree. They had body-like trunks and leaves like flowing hair. In the spring, long shafts appeared in the centre of the plants and everyone recognised the spirits of Yaddy and his family. Yaddy's spirit was still giving them spear shafts.

How we used the yaddy (grasstree)

We ate the roots and leaf bases of young yaddy (grasstree) plants and made a sweet drink from the flower nectar. We made resin from the trunk to glue stone and wooden tools together. We used flower stems for fire-sticks and to make currawon (fishing spears), and the sharp edges of leaves for cutting. We used our fire-sticks to change the vegetation, to flush animals from the long grass for easy hunting, to crack open seed pods in the fire's heat and to reduce fuel so bushfires sparked by lightning burned slowly.

Bush Tucker Garden - Fibre - Medicine - Food

The natural environment was a hardware store, supermarket, and pharmacy for Aboriginal people. This garden features a selection of species of significance to Indigenous culture.

Leaves, stems, bark and timber were all materials used to make shields, canoes, hunting implements, string, bags, baskets and even jewellery.

The mighty River Red and Box Gum trees outer bark was carefully removed from the tree and crafted into Murrins (canoes) or Coolamons (food bowls). These scars are still present in the landscape today.

The canoe bark was held over a fire, so the sides would curl and both ends were secured with rope and wooden stretchers, to prevent the sides collapsing.

Leaves of mat rushes were split and skilfully woven by women into beautiful baskets, mats and bags.

Stems of grasses were used to make string for fishing lines, nets and dilly (string bags).

Reeds were used for jareel (spears), the leaves twisted into rope and hollow stems strung on string for decorative reed jewellery or nose ornaments.

The wood from Wattles was used for axe handles, spear throwers, murka (shields) and nulla (clubs).

We hunted and gathered all the food we needed from the wild and had a very healthy diet. We cooked our munga (food) on wongee (campfires) but often it was eaten fresh and raw.

Plants formed the staples in addition to meat, which was dependant on a successful hunt. Seeds were collected from native grasses (which were ground into flour), herbs, fruit, nuts, gums and nectar.

Women and children dug for underground tubers, roots and stems with special digging sticks and would dig for Memeeyong (Yam Daisy) which has a sweet coconut flavour when cooked.

Plants for hunting

Plants were used for stunning fish in rivers and creeks. The men could then easily catch them in nets, which were woven from grasses and rushes.

Fires encouraged fresh new grass for animals to graze and the gaps allowed room for a diverse understorey of lilies and herbs. The hunters could also more easily view their prey such as Womboyn (Grey Kangaroo).

We used all these plants and understood the right time to collect them and how to prepare them (so we did not get sick) and how to make them taste nooromunga (good to eat).

What we know about using plants has been passed down from our ancestors.

Bush medicine was used on rare occasions, with tonics used to maintain good health and to prevent us from getting sick.

Plant material including berries, bark, leaves and flowers were used to treat symptoms. Plants were infused in hot water to make a tea or wash, ointments were made using animal fat and steaming pits were used for a number of ailments.

We knew how to treat toxic plants so that they were safe.

Sometimes songs and ceremonies were conducted because we believed bad spirits had made the person sick.

Small leaved Clematis was one plant used as a poultice for aching joints of arms and legs. It is also known as Old Mans Beard because of the fluffy flowers and grass seeds.

Sneezeweed was another useful plant. It was used for common skin infections, colds and even tuberculosis. The leaves of this plant were bound around the head of the sick person.

Aboriginal people shared their knowledge of traditional medicines with the early settlers, as Medical Doctors were few on the ground. Pharmacy style medicines as we know them, were often only in big cities or at worst a boat journey to England away.

*Please do not pick or eat any of the plants from the Bush Tucker Garden*

12. Yarraboyn and Womboyn - Red Kangaroo and Grey Kangaroo

The Yarraboyn and Womboyn story speaks of the strong and meaningful relationships between neighbouring tribes in sharing and trading resources. This story relates to the origins of the red and grey kangaroo and the importance of building relationships and sharing between different cultural groups and communities.

13. Yirradwor - Magpie

Once there was a Pangerang family who had very mischievous twin boys. The Elders of the clan told the parents they must paint white ochre onto the back of one maldiga (boy) so everyone could tell them apart.

One day, the clan joined a neighbouring clan for a meeting and corroboree and discovered the neighbouring Elders were having similar issues with twin girls. The neighbouring Elders decided to paint the back of one meegay (girl) with white ochre.

Years later, the boys met the girls. It was love at first sight and they asked to marry. Eventually the Elders decided the twins could marry, however the white-backed ones were to marry each other and were to keep their backs painted with white ochre until the Elders of both clans were satisfied they could be trusted to behave.

After the two sets of twins married, their mischievous ways began to reappear, only this time it was double trouble. This almost caused a war between the clans. Just as the first boondithurra (spear) was about to fly, a dark cloud filled with tumbarumba (thunder) and Mikkee (lightning) suddenly appeared above and Byamee himself stepped down from it.

He stared at both sets of twins, reached out and grabbed the white-backed couple with one murra (hand) and the black-backed couple with the other, holding them high so everyone could see.

Byamee told the white-backed couple to stay to the south and west, and the black-backed couple to stay north and east. Then he threw them into the sky and away they flew. He had changed them into Yirradwor (magpies)!

If you are ever travelling south west toward Bendigo, you will notice all the magpies have black backs until you reach a town called Goornong. From then on, you will notice all the magpies have white backs. Now you know why!

14. Jareel - Life by the River

This river environment was rich in wildlife and plants. It sustained our traditional ways of living for thousands of years.

We hunted willee (brush-tailed possums) and boogahree (ringtail possums) and ate their meat, made their teeth into needles and sewed warm cloaks from their skin.

We stripped bark from black wattle trees, soaking it in water to tan kangaroo and possum skin hides.

The reeds growing along the banks of the Torryong made good jareel (thin fishing spears). We hollowed out the end of the reed and used beeswax to hold in the spear-head. We traded spears with other groups, often for stones from the other clans' areas.

We threw boomerangs above ducks, to help herd them into our waiting nets strung across the river.

We took wood and bark from the trees and carved it to make murkas (shields) and murrins (canoes), and we feasted on freshwater bukaar (mussels) cooked over riverside wongeys (campfires).

15. Identity

Eddie "Kookaburra" Kneebone was a Pangerang Elder and Aboriginal Reconciliation campaigner, teacher and painter. In 2001, Eddie received the Pax Christi International Peace Prize for his work. He created cultural awareness programs through education and his art.

"Because of history and the events which shaped the situation today, as Aboriginal people we are continually discovering ourselves. We are not one group indigenous of this (North East Victoria) region but we are the survivors of history and its devastation. We are a multiracial group intermingled with every other group because we needed to survive, we are the first generations of the future.

Today, 240 years later, the remnants of the clans of the region face their greatest challenge to exist in the future as identifiable people known as Indigenous. The Indigenous community today are neither black or white, one or the other, they are in the middle of two cultures. As Aboriginal, we are endeavouring to find a place in a society that for 200 years has restricted and ignored us. Although the doors are now open and access freely provided, there is still the learnt behaviour of history, which restricts us in our thinking. On the other hand because we are of mixed race, the non-Indigenous identity is trying to find its place and belonging in this country. The colour of your skin is important to your identity but it is not important in your understanding of who you are. We are all humans." ~ Eddie "Kookaburra" Kneebone

Access for Dogs:

Dogs are permitted on leash on the trail. North of point "12. Yarraboyn and Womboyn - Red Kangaroo and Grey Kangaroo", the area becomes an off-leash area.

Review:

This is a special walk which follows the Ovens River and has magical Indigenous artwork and signage with enchanting stories.

Photos:

Location

1 Bickerton Street, Wangaratta 3677 View Map

Web Links

→ culturewangaratta.com/bullawah-trail

→ Bullawah Cultural Trail Brochure (PDF)

→ www.visitwangaratta.com.au/See-Do/Arts-Culture-History/Bullawah-Cultural-Trail

→ Bullawah Cultural Trail (Walking Maps)