Bataluk Cultural Trail (East Gippsland)

The Gunaikurnai people of East Gippsland invite you to visit the sites along the Bataluk Cultural Trail.

These are landscapes where you will be introduced to aspects of Gunaikurnai history and culture including Dreamtime stories, traditional lifestyles, European invasion and settlement and present day life.

Borun and Tuk, the Pelican and Musk Duck are the creators of the Gunaikurnai people. The Bataluk Cultural Trail follows significant traditional routes used by the Gunaikurnai for over 30,000 years. With the mountains a two or three day walk to the north and the lakes and ocean one or two days walk to the south, the path which is now the South Gippsland and Princes Highways formed the backbone of the network of trails and trading routes which spanned the region.

Initiation rites for young Gunaikurnai men and women in East Gippsland in the past consisted of a progression through several stages. Initiation ceremonies were major events attended by all clans. Ceremonies would last for five days and entrance to a higher tier of knowledge and understanding was only granted when participants had reached an appropriate level of commitment and readiness.

Your journey along the Bataluk Cultural Trail will involve a similar process. The trail can be experienced in a variety of ways; you can travel from one end to the other, or you can select from the range of sites and activities to design a route, which suits your own particular interests.

The Bataluk Cultural Trail will introduce you to many aspects of Gunaikurnai life. The more time you spend and the more places along the trail you are able to visit, the greater your appreciation and understanding of Gunaikurnai culture and heritage in East Gippsland.

For a variety of reasons such as environmental or historical sensitivity, some sites in the region are not appropriate for unrestricted access by members of the general public. We ask that you treat all sites along the trail with respect and care, to ensure that they are preserved for future generations.

Bataluk is a Gunaikurnai (pron. gun-i kurn-i) language word for lizard and the trail winds through East Gippsland like the tail of a lizard...

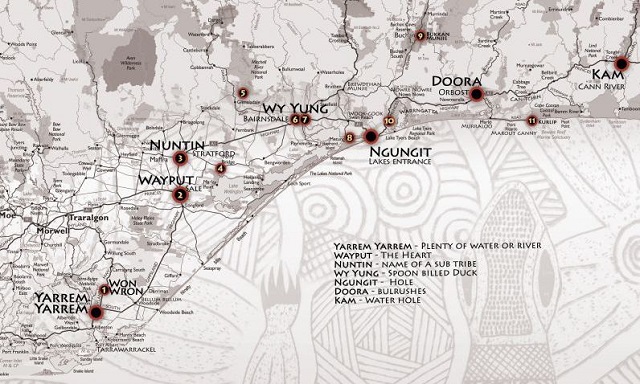

Bataluk Cultural Trail Map

Sites

1. White Woman's Waterhole (Won Wron State Reserve)

Captive or a devious fiction? Perhaps the biggest story to come out of Gippsland in the 1840s was the search for a lost white women said to have been held captive by some Gunaikurnai people.

Local legend has it that in the 1840s, a young woman, the sole survivor of a shipwreck off the nearby Ninety Mile Beach was taken and held captive by the local tribe of Bratwoloong, who inhabited this part of Gippsland.

Angus McMillan, an explorer who later squatted on land in Gippsland for his own pastoral requirements, started this story in the 1840s, with a letter to the Sydney Press. McMillan claimed he had come across a deserted Gunaikurnai camp strewn with an array of items, including female clothing and a dead baby, said by a Dr. Alexander Arbuckle to be a white child.

The story of the captive white woman developed a life of its own, spawning numerous myths, with various versions even claiming a sighting of a white woman being hurried away. This lead to search parties consisting of Angus McMillan's men and Native Police pursuing Gunaikurnai people to try to rescue her. The woman, if she ever existed, was never found. A ship's figurehead however, was recovered, leading to speculation that it may have been mistaken for the white women.

This White Woman of Gippsland story is believed to have been used to justify the killings of many Aboriginal people, particularly the Gunaikurnai. Massacres of the Gunaikurnai led by McMillan occurred at Nuntin, Boney Point, Butchers Creek, Maffra and at other unspecified locations throughout Gippsland. A massacre at nearby Warrigal Creek is recognised as one of the worst in Australian settlement history.

The White Woman's Waterhole commemorates the tragedy of this story.

2. The Lagoon (Sale Common State Game Reserve)

Like a Supermarket. The wetlands may be reached either via Lake Guthridge, which is right beside the Princes Highway/South Gippsland Highway intersection in Sale, or by turning off the South Gippsland Highway about 1km out of town. The turnoff is well signposted. Further information may be obtained at the Sale Visitor Information centre.

The wetlands were like a supermarket for the Gunaikurnai people of the area. A walk around Lake Guthridge to the Sale Common boardwalks reveals numerous plants and birds which were sources of food and other important raw materials.

Gippsland Redgum (Eucalyptus tereticornis subsp. mediana) - The wood was much prized for making boomerangs, shields and weapons. The bark was used for canoes, shields, infant carriers and for wrapping up the deceased. Burls were cut to make bowls. The seeds were eaten and the sap was used as medicine to treat burns and diarrhoea. The tree also provided a look-out and habitat for other food sources and resources such as birds, beehives and possums. Prior to European settlement, most people in Victoria wore a possum skin cloak. Gippsland Redgums can live for over 1000 years. Scars are created when the Gunaikurnai removes bark for a canoe. Scar trees are living heritage and are protected under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006.

3. The Knob Reserve (Stratford)

Axes and fish hooks. Meetings past and present - On the bluff high above a bend in the Dooyeedang (Avon River) axe heads were sharpened on the sandstone grinding stones. The deep grooves, which may still be easily observed, are a reminder of the ancestors who have visited this place for centuries.

When the stones were ready they were bound with kangaroo sinew to a handle of supple wood which had been treated in a fire to harden it.

Down by the river people fished for eels, bream, flathead and prawns which were an important part of the food supply. Spears, nets and hooks made from kangaroo bone were used to catch the fish.

The bluff above the Dooyeedang was a major campsite and meeting place for the Gunaikurnai people who have lived in this region for thousands of years.

It provided an ideal vantage point from which to look out for fish, animals or other groups of people. As well as being a source of food, the Dooyeedang was a major transport route for the Gunaikurnai people. Bark canoes were used for fishing and travelling up and down the river between the mountains and the lakes.

This was a well sheltered campsite, close to the river and fertile river flats that supplied plenty of good food and water and would have allowed large gatherings of clans from the Gunaikurnai nation to meet for feasting, corroborees and other ceremonies.

Migration routes along the river and along the present day highway passed close to this camp.

A meeting Place Again - Around the turn of the century, this area was used for less happy meetings.

In 1886 all 'full blood' Aborigines were forced by law, to live in missions. Aboriginal people of mixed descent were classed as 'non-Aboriginal' and not allowed contact with their parents or other relatives.

In secret and in fear, Aboriginal people would walk the 15 km from Ramahyuck mission, at the mouth of the Avon River, to meet with their relatives at this traditional gathering place.

At this place in 2010 a Native Title Agreement was signed. The determination area covers approximately 45,000 hectares in Gippsland extending from west Gippsland near Warragul, east to the Snowy River, and north to the Great Dividing Range. It also includes 200 metres of offshore sea territory. The determination area includes 10 parks and reserves that are to be jointly managed by the Victorian government and the Gunai/Kurnai people.

4. Ramahyuck Cemetery (Perry Bridge)

In the early 1860s the Moravian missionary, Frederick Hagenauer established a mission station on the Avon River near Lake Wellington. Hagenauer named the mission Ramahyuck; Ramah: Hebrew for 'home' and yuck: Aboriginal for 'our'

At Ramahyuck the Gunaikurnai gave up their freedom and culture for (as the Europeans saw it) protection, food and Christianity. Hagenauer was hardworking and authoritarian and did not allow any tribal customs or ceremonies.

After 1886, Hagenauer was feared throughout Aboriginal Victoria for his role in the forced expulsion of 'half-castes' from missions and reserves. Hagenauer encouraged non-Gunaikurnai Aboriginal people to move to Ramahyuck, such as Nathaniel Pepper from the Wimmera and young women from Albany in Western Australia.

From 1905 until 1908 when Ramahyuck was closed, Aboriginal people from this mission were moved, some against their will, to Lake Tyers Mission.

The Devastation of the Half-Caste Act - The 1886 Aborigines Protection Act required Aboriginal people of mixed parentage and who were under 35 to leave missions and reserves. This included the Gippsland mission stations of Ramahyuck and Lake Tyers.

The Half-Caste Act was a crude attempt at assimilation in the expectation that within a generation or two Aboriginal people would merge into 'mainstream' Australia, being unrecognisably Aboriginal. It was an attempt to remove Aboriginal people from their families and to destroy their connections. Its effect was to push 'half-castes' into an environment without the advantage of extended family resources or skills. The Half-Caste Act caused much social distress, split families, exiled children, disrupted marriages and forced 'full-blood' people to leave long established homes for the sake of staying with children and grandchildren.

Very little remains of Ramahyuck Mission Station today, from a property of over 2000 acres only the cemetery is left.

We ask that you do not walk on the graveyard, as you may be walking over many unmarked grave sites.

5. Den of Nargun (Mitchell River National Park)

The Nargun is a large female creature who lives in a cave behind a waterfall in the Mitchell River.

The Den of Nargun is a place of great cultural significance to the Gunaikurnai people, especially the women.

Stories were told around campfires about how the Nargun would abduct children who wandered off on their own. The Nargun could not be harmed with boomerang or spears. These stories served the dual purpose of keeping children close to the campsite and ensuring that people stayed away from the sacred cave.

The Den of Nargun is a special place for women and may have been used for women's initiation and learning ceremonies.

The walk into the Den takes approximately 15 minutes each way, or 45 minutes as a circuit walk via the Mitchell River. Note that there are some steep sections along the walk.

The Mitchell River National Park - The Mitchell River National Park holds a rich cultural history which tells stories of conflict between tribes, ceremonies, food gathering, community life and spirits that inhabit the area.

The Mitchell River National Park has the southernmost occurrence of dry rain forest with its dominant species of Kurrajong found on the rocky slopes of the Mitchell River Gorge. The park has special conservation values with several significant communities and a number of rare and threatened species of State and National significance. Twenty regionally significant species are found.

Alfred Howitt was the first European explorer to survey the river accompanied by two Aboriginal guides, Bungil Bottle and Master Turnmite. Howitt travelled down the Mitchell River in a bark canoe. When they reached the rapids they were forced to abandon the canoes and travel up Woolshed Creek where they discovered the Den of Nargun.

The Mitchell River is part of a 260km system, making it Victoria's largest remaining wild and free flowing river. It flows from the Great Dividing Range where the Wonnangatta and Dargo Rivers meet, to its mouth feeding the heart of the Gippsland Lakes near Paynesville. The Mitchell River is heritage listed.

The Mitchell River is the dividing boundary between the Brabawooloong clan to the east and the Brayakooloong clan to the west.

6. Krowathunkooloong Keeping Place (Bairnsdale)

History, Heritage and Culture - Since the time when Borun and Tuk founded our people, the Gunaikurnai hunted the animals and gathered the fruits of a vast natural wilderness. This land fed, clothed and sheltered us. At times this land was generous, at other times cruel. To our Ancestors, life was a constant test of the weapon maker's skills, the hunter's endurance and the tireless explorations of the gatherers.

Our Gunaikurnai territory was sheltered by tall mountains to the north and west and watered by its many rivers that flowed fully through the coastal plains to the estuaries and into the ocean. This land fostered our clans, the creation of our language, our rich mythology, laws, social customs and skills in craft and artifacts. Our Land was our Mother.

For thousands of years Aboriginal people have cared for their sacred sites and objects. They would visit these places at significant times throughout the year to hold important cultural ceremonies. Sacred sites and objects held religious significance and the Elders were responsible for their guardianship.

The Krowathunkooloong Keeping Place endeavours to preserve and share this guardianship and responsibility with all local community members.

The Krowathunkooloong Keeping Place is named after one of the five clans of the Gunaikurnai. Krowathunkooloong is is the name of the Gunaikurnai tribe that occupied the Orbost area.

The Keeping Place was named during 1991 and officially opened in 1994 and aims to raise the profile and awareness of the Gunaikurnai people's history of the Gippsland area and to build a better understanding of Aboriginal culture, history and heritage. It provides a recognizable and centrally located complex and facilitates greater community awareness, understanding and pride in Aboriginal culture, arts and crafts.

Visitors to the Keeping Place can learn, understand and appreciate the history of the Gunaikurnai people through guided or self-guided tours of the museum. The display includes traditional hunting and fighting weapons, bark canoes, baskets, fishing spears, boomerangs and an exhibition of contemporary Gunaikurnai art. There are staff members on hand to answer questions.

The Keeping Place is located at the western end of Bairnsdale. Signposts clearly indicate where to turn off the Princes Highway. Open Monday to Friday from 9am to 5pm. Group bookings may be made on 03 5152 1891.

The Keeping Place is also home to the Gippsland and East Gippsland Cooperative which provides a range of programs and sevices. GEGAC holds divisions for Administration, a Medical Centre, Dentistry, Child Care, Elders Centre and Family and Youth Services.

7. Howitt Park (Bairnsdale)

When the Golden Wattles bloom - The Park is located beside the Princes Highway at the eastern end of Bairnsdale, across the Mitchell River. It has a range of facilities for the motoring traveller.

When the golden wattles were in bloom it told the people that it was time to harvest the eels which were plentiful and fat at that time of year. Some of the women put finishing touches on baskets woven from cumbungi reeds. These were used for collecting fruit, roots and mussels. The baskets were very durable and could last for up to one hundred years. On a small rise overlooking Wahyand (Mitchell River) the men made a canoe. The 4m long scar made when the bark was peeled away can still be seen on the tree in Howitt Park. It is believed that this tree is approximately 170 years old.

The scarred tree at Howitt Park is a canoe tree and is protected under the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006. The stand out features are the height and size of the scar on the tree.

8. Legend Rock (Metung)

Hunters turned into stone - The Legend Rock, an important part of Gunaikurnai mythology, lies in shallow water by the shore of Bancroft Bay, opposite the Metung Yacht Club in Tatungooloong Country.

One day, some fisherman who had hauled in many fish with their nets, ate their catch around their campfire. The women, guardians of the social law, saw that the men had eaten more than enough but had not fed their dogs. As a punishment for their greed the fishermen were turned to stone.

This story is one of many Gunaikurnai stories that were told and retold to show that greed would bring punishment.

The Legend Rocks hold great spiritual value to the Gunaikurnai people and the story serves as a great legend for its people to remember the laws of the land.

There were originally three rocks in the formation at Metung, unfortunately two were destroyed during road construction along the shore of Bancroft Bay in the 1960s. The last rock was preserved when community members and Gippsland & East Gippsland Aboriginal Cooperative had an injuction issued. The Legend Rock continues to be protected under the Heritage Act of Victoria.

Turn off the Princes Highway at Swan Reach and follow the Tambo River, well signposted.

9. Buchan Caves (Buchan)

18,000 Years Ago - Archaeology has shown that Aboriginal people have lived in the Buchan region for around 18,000 years.

A nearby cave contains artefacts and evidence of Aboriginal occupation of 18,000 years ago, making it one of the oldest Ice Age (23-10,000) cave sites in south east Australia. Repeated or long-term camping activities were undertaken throughout the Buchan region.

The Snowy River valley is rich in archaeology sites. The most common type of sites recorded so far are surface scatter of stone artefacts. Some of these sites are rather large, containing up to 1,000 artefacts over hundreds of square meters.

Traditional Tour Guides - Aboriginal people played a vital role in European exploration and settlement of the Snowy and Buchan Valleys. They acted as guides and were employed as stockmen on many early runs in East Gippsland and the Monaro plains in NSW.

However within 50 years of European settlement, traditional lifestyles had all but been destroyed through disease, dispossession from hunting grounds and warfare.

Aboriginal communities in East Gippsland and the NSW coast continue to have strong ties with the area.

Traditionally Gunaikurnai people did not venture deep into the limestone caves at Buchan. There were, however, many stories about the wicked and mischievous Nyols which lived in the caves below the earth. Tribal memories of that time may be detected in the story which concerns a group of children who inhabited this area when there was known to be a land south of Gippsland where there is now sea (ie Tasmania). When playing they found a sacred object which they took home and, against traditional law, showed to the women. Immediately the earth crumbled away and it was all water and many people were drowned.

Staff at Buchan Caves run regular tours into the caves throughout the year. There is an attractive caravan park within the Park boundary.

10. Burnt Bridge Reserve (Lake Tyers Forest Park)

A bush pantry - The local plants and animals gave the Aboriginal people of this area, the Gunaikurnai, most of what they needed. Many different plants were used for food and medicines and to produce woven baskets and nets and in the manufacture of tools and weapons.

The underground tubers of Water Ribbons (Triglochin procera) are still a popular food in Aboriginal communities throughout Australia.

Silver Banksia (Banksia marginata) flowers were soaked in wooden bowls to make a sweet drink.

The young leaves of Pigface (Carpobrotus spp.) were eaten raw or sometimes cooked with meat. The red fruits were also eaten.

The hard wood of the wattle Blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon), was prized for spear throwers and sheilds. Its bark was heated and soaked in water for bathing rheumatic joints. The strong inner most fibres of the bark were woven into string for fishing lines.

A hard waterproof resin can be collected from the base of Grass trees (Xanthorrhoea spp.) without damaging the plant. Softened by heating, it was used to fasten axe heads and spear points and for many other purposes.

Where? - Located down a signposted turn-off from the Princes Highway between Lakes Entrance and Nowa Nowa, the Reserve is situated adjacent to land belonging to Lake Tyers Aboriginal Trust. A display centre on site provides information about Lake Tyers.

11. Salmon Rock and Gunai Boardwalk (Cape Conran)

Middens in East Gippsland have been dated at over 10,000 years old.

Turn south off the Princes Highway at Orbost to Marlo. From there take the Conron Road east to the Cape.

The viewing platform at Salmon Rock is built above an Aboriginal shell midden; the top layer is visible. A shell midden denotes a special site or meeting place where people have gathered regularly for many generations to feast, celebrate and perform ceremonies. Middens in East Gippsland have been dated at over 10,000 years old. Even today, Cape Conran remains a special place for the Gunaikurnai people of the area to visit throughout the year.

West Cape - A Coastal Life - This part of the coast contained an abundance of food for the Gunaikurnai, with many important sites all along the beaches of the Cape Conran area.

Shell Middens are important cultural sites to the Gunaikurnai and can be found throughout this coastal area. Shell Middens are mounds or 'rubbish tips' where the Gunaikurnai have sat in one area for a constant period of time and left or thrown away their rubbish. Eventually this rubbish tip builds up with many different tools and species of marine life remains such as the shells of oysters, mussels, crayfish, fish bones and pippies.

East Cape - A Meeting Place - This part of the coast is near the traditional border of the lands of the Gunnaikurnai people and the Bidawal and Monero people. The picturesque nature of the cape here, along with an abundance of food and the availability of ochre for ceremonies have made it an ideal meeting place for these groups.

The people of Moogji Aboriginal community invite you to discover more about Aboriginal culture as you make your way along the boardwalk.

This site is particularly important for Aboriginal people and part of the heritage of all Australians. Aboriginal sites are protected under the Heritage Act 2006. It is an offence to tamper with or remove anything from an Aboriginal site.

The boardwalk protects important Aboriginal sites, while giving good access to the coast. It has been constructed by the Moogji Aboriginal Council in liaison with Parks Victoria and A.N.C.A.

Location

37 - 53 Dalmahoy Street, Bairnsdale 3875 View Map

✆ (03) 5152 1891

Web Links

→ batalukculturaltrail.com.au

→ Krowathunkooloong Keeping Place (Bairnsdale)