ANZAC Walk (Emerald)

Emerald's 30 minute Anzac Walk features plaques, information signs and an audio trail to listen to the stories of the 32 soldiers from Emerald and how they died in the war plus a statue of the Unknown Soldier. The walk starts at the cenotaph on the corner of Kilvington Drive and Belgrave-Gembrook Road and finishes at Anzac Place near the Emerald RSL.

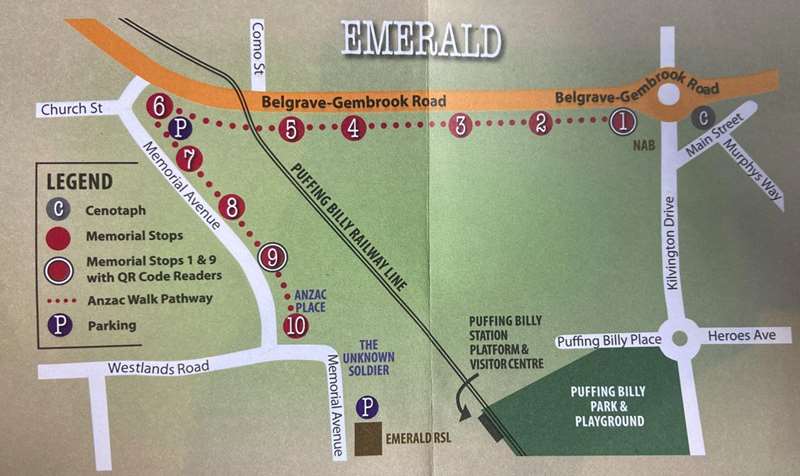

Map of Route

Transcript of Audio Walk

Stop 1: Emerald and Then War

The year 1914 saw the Emerald community flourishing. Good rains had caused good crops and farmers were smiling. And the backdrop to this thriving community was Carl Nobelius' Gembrook Nurseries.

At its peak the nursery spread out over many hundreds of acres as far north as Nobelius Street, south to Paternoster Road and included much of the present-day Emerald Golf Club and Emerald Lake Park. Nobelius employed up to eighty local and itinerant workers and had millions of trees for sale to a worldwide market. All that is left now of this once great nursery is the ten-acre Nobelius Heritage Park located at the end of Crichton Road, Emerald.

Where we now stand became part of the town centre. Within sight of the train station was the 'Smithy' Charles Stapleton and the Coffee Palace, a guest house for some of the itinerant workers run by Emma Foxford. As the township grew, land around the Coffee Palace was subdivided and sold off.

Further out, Brookdale Farm, hosted by Councillor Robert Ferres and his family and Mr and Mrs D'Ombrain's Avonsleigh House were vibrant social resorts, where the women put on concerts and weekend celebrations that attracted visitors from around the state. Up in his mansion, Carl Nobelius entertained such dignitaries as Dame Nellie Melba and the Victorian Governor.

In such a small community town it meant everyone knew everyone and life was good.

Then war was declared and Australia called on a generation in its hour of need. The Argus newspaper said it threatened to be the greatest war of all time, and Britain asked for 18,000 troops. Australia's Prime Minister, Joseph Cook, promised 20,000.

Blacksmiths, butchers and butter-makers, farmers, gardeners and labourers, orchardists, horticulturists and bushmen downed tools to answer the call.

And amid the excitement of a generation picking up their guns and taking their homeland military training skills into a real war, each of these community hubs was to be affected. More than 100 people working and living in this community enlisted to fight.

Carl Nobelius struggled to cope. Many of his workers enlisted, international markets closed down and the financial strain began to tell.

Emma Foxford saw her two sons and her husband go off with some of those itinerant workers boarding at the Coffee Palace.

Brookdale Farm continued its New Year and Easter celebrations in spite of the war. But even the Ferres family could not insulate itself entirely.

Now walk down this avenue of honour as it takes us back to acknowledge the sacrifice of those who died. Remember them in the belief that they will only be truly dead when their names have been spoken for the last time.

But also, find a thought for those who answered the call and came back only to suffer the effects of war long after it was over.

Stop 2: The Glory of Anzac Cove

EDGCUMBE, James Adolphus (Private) KIA 1915 24yrs

FERRES, Sydney Eversley (Private) KIA 1915 26yrs

WALKER, Thomas (Private) KIA 1915 21yrs

WRIGHT, Sydney (Private) KIA 1915 >23yrs

-embed01.jpg)

Just before dawn on 24 April 1915, James Edgcumbe, Syd Ferres, Syd Wright and Tom Walker slipped over the side of their transport ship with their battalions and onto the glassy smooth surface of the Aegean Sea. They were going to war.

As their boats began to beach in what was to become Anzac Cove, the zing-zing-zing of Turkish bullets fizzed in the water. Almost immediately James Edgcumbe was wounded, then went missing, then was lost forever in the craggy gullies of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Syd Ferres, Syd Wright and Tom Walker continued their assaults on the Turkish enemy until their battalions were ordered south to Cape Helles to fight alongside the British. Arriving on May 8, they were ordered straight into battle, but by day's end Syd Ferres and Tom Walker were dead. Only Syd Wright survived to be ordered back with his battalion to Anzac Cove where he, too, succumbed to a hail of Turkish bullets in The Battle of Lone Pine.

Back in Australia, Prime Minister Andrew Fisher was telling the people that the soldiers were in action at the Dardanelles. The newspaper headline read: "The glory of it" and people cheered.

But the families of these Emerald soldiers did not yet know their boys were dead. Any glory they may have felt would soon disappear when they learned of their fate. All four lay somewhere under the soil of the Gallipoli Peninsula and would never be found.

Stop 3: Their Duty Nobly Won

WRIGHT, Frederick (Corporal) KIA 1915 26yrs

DURANCE, Eric William John (Private) DOW 1915 21yrs

COATES, Percy John Curtis (Sergeant) DOI 1916 25yrs

SAWERS, Stanley Sydney (Private) KIA 1916 23yrs

As the battles raged on the Gallipoli Peninsula and soldiers were dying, Corporal Fred Wright fought long enough to be mentioned in despatches for his bravery and was then killed. In Australia, the reality of war was beginning to hit home, and it would hit none harder than Emerald's Eliza Wright when she was told that both her sons were dead.

With thousands dead and dying, soldiers from both sides began wondering what it was all for. The Australians had advanced a kilometre and were not going much further. The diggers and Johnny Turk became reluctant to fire at each other. It was a stalemate. Just as the Generals acknowledged a time to withdraw, 21-year-old Macclesfield farmer, Eric Durance was hit in the head by shrapnel and died. The Anzacs withdrew as Eric's family were told of his death and mourned.

Percy Coates survived Gallipoli to be one of the first Australian soldiers to arrive in France. It was a different welcome for the Australians. They were not the enemy as on Gallipoli. People cheered and blew them kisses as they marched onto the Western Front. But on French soil Percy was struck down with septicaemia (or blood poisoning) and died before firing a shot. His mother, told five days after his death that he was dangerously ill, would wait another year before she was told he was dead.

For the other Australians arriving on the Western Front, the first big battle was at the village of Fromelles. The soldiers were ordered over the top at 6pm but the Germans were already on the high ground and sprayed them with machine-gun fire from three sides. At 7pm soldier Les Summers saw his mate and Nobelius employee Stan Sawers hanging over the parapet. He squeezed his hand, but it was icy cold and there was no response. Stan had lost his life in the first volley of gunfire and his body would be swallowed up by the battlefield. And, again, it would be more than a year before his mother would find out.

In ten hours of military chaos 5,533 Australians were killed or wounded in what was only a diversionary tactic. Then the order was given to leave the dead and wounded on the battlefield.

Stop 4: Up Hill Never to Return

FELL, Harold Victor (Private) KIA 1916 24yrs

FULTON, Arthur Leeman (Major) KIA 1916 21yrs

BARNES, Charles Spencer (Private) KIA 1916 24yrs

BARNES, Harrie Hasler (Private) KIA 1916 30yrs

Further south the British had been well beaten at Pozieres on the Somme and now it was Australia's turn to have a go. Cockatoo Creek's Harold Fell was on the front Arthur Fulton and the Barnes brothers. Again, the German enemy had the high ground and again, the Australians were charging up hill.

After some fierce fighting and amid heavy shell bombardment, Harold Fell's company retreated from the front line. But back in Sausage Gully, their refuge behind the lines, the Cockatoo bushman was not among them; he had been buried by bombardment and another life lost forever in the Somme mud.

At the height of the battle, 24-year-old Charlie Barnes was fighting alongside his brother 30-year-old Harrie when they were killed by a shell explosion. The other soldiers buried the brothers in a hole on the battlefield and in that instant, their sister Lucinda was left the lone family member. Back in Australia, Lucinda, and Charlie's fiance Elsie Muir were waiting. All that was left was to tell them that their boys were dead.

Throughout August and September of 1916 the Australians pushed the German Army back across the Somme landscape amid gunfire and high explosive shell bombardment. Major Arthur Fulton, out on the front line leading his B Company in the Tramway Trench, was suddenly hit by field gun fire. It killed him instantly and the shell bombardment buried him in a moment. He, too, would never be found.

Stop 5: Maybe for a Better Land

HALES, Harold George (Private) KIA 1916 19yrs

LADD, Edward Wildes Holyoak (Sergeant) DOW 1917 28yrs

SHANKS, George Charles Robert (Private) KIA 1917 22yrs

PAGE, Raymond Samuel (Sergeant) KIA 1917 24yrs

As the Battalions charged onto the battlefields of the Somme, 19-year-old apprentice nurseryman Harold Hales was hit by machine-gun fire. The stretcher bearers carried him to a clearing station where he slowly died. Then the battles on the Western Front petered out with winter and year's end. Mugs of tea froze over and the soldiers couldn't cut their bread with a knife, yet the killing went on into 1917.

On April 6, Ted Ladd, an engraver from Upper Beaconsfield, was wounded just outside the village of Tullecourt. His mates got him back to a clearing station but he died the next day. The Emerald Rifle Club acknowledged his de in the newspaper.

George Shanks, an Upper Beaconsfield orchardist, went missing and was then declared dead while fighting at Queant. He was another lost and how he died would never be known. Back in Australia George's aunty and his cousin Dorothy tried to make sense of it saying: "Not now, but in the coming years, it may be in a better land, we'll read the meaning of our tears, and then, oh! then, we'll understand"

But there was no time to understand. The diggers were ordered forward to face fierce fighting around the village of Lagnicourt. Where once there were green fields, there was only mud and shell holes. And as the battles pushed into May, Sergeant Ray Page died fighting on that barren land just just to the right of Bullecourt; and his family too had to try to make sense of it.

Stop 6: Thy Will be Done

LAMBORN, Bruce Robison (Corporal) KIA 1917 26yrs

MOFFATT, Francis Angus (Private) KIA 1917 27yrs

PARKER, Harold Hill (Private) KIA 1917 24yrs

CLARK, William Thomas (Private) KIA 1917 33yrs

Deep into the second half of 1917 the Allied forces moved into Belgium in what was known as the Flanders Offensive. They found their sustenance chewing on forty-niners. These were biscuits the soldiers reckoned took 49 years to bake, had 49 holes in them and took 49 chews to a bite. Fed on the forty-niners, Bruce Lamborn advanced with the 2nd Division Trench Mortars into the Battle of Menin Road. He didn't come back; killed in action on September 5. The army sent his father a letter saying they'd buried him in the Huts Cemetery at Dickebusch.

Emerald telegraph operator, Frank Moffatt moved through Chateau Wood with his battalion clearing out concrete bunkers and burying the German dead. But he, too, became one of the dead and one of the thousands remembered with his name on the Menin Gate. His family expressed their sorrow in Latin: Requiescat in pace.

Avonsleigh farmer, Harry Parker was in Black Watch Corner about to attack the German positions in Polygon Wood. At 5:53am the troops advanced behind a barrage of support artillery and Harry went missing in action. His mother heard nothing from the military and English girl Bertha Prosser went searching. Writing to the Red Cross, she found the news she and Harry's family were dreading; Harry was dead. His soldier mates recalled: Wilson told me he had seen Parker lying wounded at Polygon Wood. He died shortly after. His body was finally found in 1926 and buried in the Hooge Crater Cemetery, Belgium.

Tom Clark was hit by shrapnel on Passchendaele Ridge, died, and was swallowed up by the mud while his children little Dorothy and baby Willie played happily in the paddocks of Emerald. Little Dorothy, when she was older, told how Aunty Elsie had said: He is peacefully resting with God. And my Grandma and Grandpa put in the paper: What though in grief we sigh for one we love, no longer nigh; submissive still would we reply, thy will be done.

Stop 7: Someone to Pray for Them

FOREMAN, Lister Beryl (Private) KIA 1917 26yrs

FELL, Francis Rupert (Frank) (Private) KIA 1917 22yrs

CULLEN, Frederick Whitehead (Driver) KIA 1917 26yrs

BOYLING, Gilbert Morrison (Private) KIA 1917 32yrs

In October 1917 Belgium was cold, wet and ravaged by war. It had been less than a month since Emerald nurseryman Lister Foreman stepped onto the battlefield alongside pastry cook Frank Fell. The Australians were pushing the Germans back towards the Hindenburg Line around Messines, Ploegsteert, Passchendaele and Ypres. At 6am they attacked on Passchendaele Ridge. Lister Foreman and his mates began digging themselves in when a German shell killed him instantly. The other soldiers buried him on the battlefield just as Frank Fell went missing. Back in South Melbourne Lister's widowed mother was given the grave news. But in Cockatoo the Fell family, already grieving for one young son, would never know what happened to Frank, as he would never be found.

Cockatoo sawmill hand, Fred Cullen was a driver on the battlefields of the Flanders Offensive when he lost his life on October 19. He was buried in the White House Cemetery, St Jean-Les-Ypres, Belgium. When his brother asked for pictures of his grave, the army said that there would be a cost of one shilling and six pence before they could send to London for the pictures.

War fizzled into December and both the Germans and the Allies prepared for another cold Christmas winter. Only sporadic shelling and firing happened to keep each side honest. Signaller and young Emerald farmer, Gilbert Boyling, moved up to Red Lodge with his battalion as support. He settled in the signal office leaning back against the wall to rest. Suddenly a high explosive shell hit the office and the roof fell in on him. His mates dug him out. Harry Ladd recalled: An H.E. Shell exploded killing him instantly. I helped bury him at Red Lodge near Warneton. There was no cross erected at the time of my departure...

Gilbert's father Reverend Boyling and his mum Grace had prayed for many in this Great War. Now they needed someone to pray for them.

Stop 8: My Dear Son Where Are You

HOLLIDAY, Francis Bewley (Private) KIA 1918 37yrs

RUSSELL, James Harold (L/Corporal) DOW 1918 22yrs

COULSON, Harold (Private) KIA 1918 21yrs

HEPPNER, Walter Gordon (L/Corporal) KIA 1918 21yrs

Snow fell on Christmas 1917 in Flanders Fields. F rank Holliday, Walter Heppner, Jim Russell and Harry Coulson marched into 1918 but things were different. Russia had imploded into civil war and all the German military might on the Eastern Front was heading west.

In March, behind a cloud of gas, the German storm troopers arrived and as the British fought, the Australians left Belgium to support them. Frank, Jim, Harold and Walter moved south with their battalions.

They marched for a week in constant rain. Frank's battalion took a defensive position at Lavieville; but one in the battalion was already dead. They buried Frank Holliday 1.4 kilometres south west of Millencourt and 5.6 kilometres south west of Albert. It would be another two years before his family would be given those co-ordinates; a spot they could never find.

On April 25, Jim Russell's 59th Battalion attacked the small town of Villers-Bretonneux. The soldiers attacked in a pincer movement, taking the town in swift precision. But Jim's life was taken in return; wounded in the attack he died four years later.

On July 4, one of the most significant examples of warfare set new battle standards. In 93 minutes the strategic village of Le Hamel was taken, but the cost for Emerald was the life of English orchardist, Harold Coulson. A year since, his mother had written to him for news asking: My dear son, just a few lines to answer your welcome words. 1 was pleased to hear you are well and happy, hoping your teeth will be alright when you get them in... How is it you have not enlisted, have you been rejected or what?

Harold had enlisted and the next letter his mother received would say he was dead.

By August the Germans were in retreat. But as the Australians pushed forward, Walter Heppner was killed on the front line at Bayonvillers in the intensity of battle. With the news of Walter's death, his family back in Emerald had the added weight of knowing his elder brother was still on the battlefield.

Stop 9: All for Australia

TSCHAMPION, Louis Edward (Trooper) DOW 1918 22yrs

EVANS, Evan Charles Russel (Private) KIA 1918 22yrs

COLLISS, Malcolm John (Private) D0I 1918 34yrs

ANDREASSEN, Andreas (Andrew) (Private) DOI 1919 33yrs

For the first time in the war, Allied strategies were on the offensive as the Australians pushed deep into German defences. They pushed to within five kilometres of the town of Peronne and the only thing standing in their way was the village of Mont St Quentin. Defended by the elite of the German army and considered impregnable by the Allied Generals, General Monash wanted it and ordered his Australian troops up the hill.

With Emerald soldiers Louis Tschampion and Evan Evans, the Australians charged. Soon after and with some satisfaction, General Monash was able to throw into the war room conversations: By the way, we're on top of Mont St Quentin. For Emerald, it cost the life of Louis Tschampion hit in the chest by a shell and Evan Evans who lost his life among the newly growing thistles just east of Peronne.

Annie Tschampion had given permission for her son to go to war. Now he wouldn't be coming home. Evan Evans had bequeathed his belongings to his mother. The contents of his kit bag were returned to her; other than her memories, that's all she had left of him.

The Australians pushed on and General Hindenburg told the Kaiser the war was lost; an armistice needed to be negotiated.

The 7th Battalion's Johnnie Colliss would never see it. He came back to Australia and died of tubercular peritonitis in Melbourne within sight of victory.

Andrew Andreassen, a Norwegian living in the Emerald Coffee Palace, got the official news of the armistice and the end of the war while training in the region of St Ledger. Andrew celebrated and saw out his first peaceful Christmas since war began. He accidentally sustained a head injury, died of concussion and was buried in Belgium. He'd done his duty, but would never get to see his adopted country again.

Stop 10: A Sacred Shadow

ANZAC PLACE

-embed03.jpg)

Anzac Place has been created as a place of sanctuary; a memorial where we can pause to reflect on Australians who have answered the call of their country in times of war. They left their families, their work, their friends, their way of life, to do as they saw fit what was right for Australia.

The strong timber posts surrounding this memorial stand as sentinels and symbolise the strength of our fighting forces. Look at these timbers and reflect on a time when Australia called on its generations of young men and women and sent them to places of conflict. Many, too many, Australians lost lives.

Anzac Place is a private space where anyone can come and quietly contemplate, remember, reflect and simply say: thank you.

DONOVAN JOYNT

The 8th Battalion's Donovan Joynt VC enlisted in the Australian Imperial Force on 21 May 1915. He was described as short and dark, with twinkling grey eyes. He was self-reliant, dogmatic, conservative and a nominal Anglican. He would become a hero.

On 30 September 1916, Donovan was shot in the shoulder during a raid on the German trenches at The Bluff in Belgium.

He recovered to fight in the second battle of Bullecourt, at the Battle of Menin Road and Broodseinde.

On 23 August 1918, in an attack near Herleville, his battalion was pinned down by intense fire from Plateau Wood. When the leaders of his battalion and the battalion they were supporting were lost, Donovan Joynt took control, brought the battalions together and led an advance which cleared the wood's approaches. He then led a bayonet charge, captured the wood and took more than eighty prisoners. He was severely wounded in the attack. For his 'most conspicuous bravery' he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

At war's end, Donovan Joynt studied sheep breeding in England and in 1920 came back to Berwick, Australia to become a dairy farming soldier settler; then later in life to become a publisher and printer.

He was a dedicated advocate of returned-soldier causes. In 1923, he became an inaugural member of Melbourne Legacy and helped to lead the club's successful campaign to have Melbourne's Shrine of Remembrance built in its present form on its present site. In retirement, he and his wife rented then bought Tom Roberts' old home, Talisman, at Kallista and lived there until they built their own home nearby. It was then that he became a member of the Emerald RSL and remained a member until his death.

His wife died in 1978. Donovan Joynt, the last of Australia's World War I VC winners, died on 5 May 1986 at Windsor and was buried with full military honours in the Brighton cemetery. He had no children.

THE LONE PINE

-embed02.jpg)

When the Australians landed at what they would name Anzac Cove, high on a ridge beyond them was a single pine tree. Because of that one tree standing, the Anzacs named the ridge Lone Pine.

In the battle that followed, the diggers and Tommy Turk fought face to face, died side by side and were buried together under the shadow of that lone pine. They fought bravely and fiercely, but with a respect for each other unmatched at any other time in the Great War.

The diggers who fought there collected pine cones, bringing them back to Australia to grow into seedlings. And in that act, they were declaring the Lone Pine a sacred symbol.

Pines from the descendants of those first seeds now stand in many places across Australia as symbols to the memory of a time and place where thousands of soldiers answered the call for their country in its hour of need.

This tree is a descendant of that Lone Pine and as you stand in its shadow, think of their sacrifice and respect the memory of those soldiers and what they fought for.

THE UNKNOWN AUSTRALIAN SOLDIER

To mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the First World War, the body of an unknown Australian soldier was recovered from Adelaide Cemetery near Villers-Bretonneux in France and transported to Australia. It was 11 November 1993. After lying in state in King's Hall in Old Parliament House, the Unknown Australian Soldier was interred in the Hall of Memory at the War Memorial. He was buried in a Tasmanian Blackwood coffin with a bayonet, a sprig of wattle and soil from the Pozieres battlefield scattered in his tomb.

At the Unknown Soldier's internment, Prime Minister Paul Keating said: Yet he has always been among those whom we have honoured. We know that he was one of the 45,000 Australians who died on the Western Front. One of the 416,000 Australians who volunteered for service in the First World War. One of the 324,000 Australians who served overseas in that war, and one of the 60,000 Australians who died on foreign soil. One of the 100,000 Australians who have died in wars this century. He is all of them. And he is one of us.

In life, the Unknown Soldier wore his uniform with pride. In death, he stands with honour to represent all Australians who have been killed in war.

BILL HOLMES

In 1941, a 17-year-old Bill Holmes forged his mother's signature and joined the army. Enlisting with the 17th Battalion, he was sent to Darwin where he witnessed many Japanese bombings over the next 23 months.

He went on to serve as a Bren gunner in New Guinea, British Solomon Islands and Bougainville before being demobbed in 1946.

Since moving to Emerald in 1982, Bill has served the Emerald RSL in a number of capacities including three times as President. As one of the last surviving WW2 veterans at Emerald, Bill has recited the 'Ode of Remembrance' at the Emerald RSL for the past twenty years; so it is fitting that he reads the Ode in this place of remembrance - Emerald's Anzac Place:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old;

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

Lest we Forget.

KIA Killed in Action

DOI Died from Illness or Injury

DOW Died from Wounds

Photos:

Location

Cnr Kilvington Drive and Main Street, Emerald 3782 View Map